“Zhuangxiu”:

Exploring the Heritage of

Chinese Urban Residential from The 1994 Interior Design Art Proposals Exhibition

Architectural Essay

2021 Fall

Instructor David Borgonjon

Contributed to RISD group zine Charting the Present: Asian Modern and Contemporary Art

A fun, easy to read essay with certain historical specificity, theoretical suggestiveness, and formal interest.

An interesting TV show "Trading Spaces" (known in China as "交换空间") was brought to mainland China in 2005. In each episode, two families are tasked to redecorate each other's homes within a limited 48 hours. They are each paired with an interior designer and given a specific budget, and the best part is that the families don't know what's happening in their own home until the "trade" is over, creating a very entertaining surprise effect. The show was so popular in the 2000s that it was said that every episode had hundreds of candidates eager to participate.

"Zhuangxiu" (装修) refers to the decoration or renovation of apartments in urban China, which involves changing furnishings, selecting furniture, arranging storage, and adding decorations. This is usually done through shopping, without the need for professional architectural training.

"交换空间" is aired on CCTV2 (Central China Television 2) and is claimed to provide "guiding home decor shopping choices and leading a stylistic fashion." The popularity of the show reflects how passionate people are about making interior changes through shopping, decorating, and styling up their homes, especially given the monotonous and standardized nature of apartment homes in China.

Tracing back to 1994, a series of postcard illustrations in Beijing Youth Daily showed similar tones for "zhuangxiu." The event was funded by an interior construction company and featured some of Beijing's most avant-garde artists. All the interventions shown in the illustrations were done in the manner of "zhuangxiu," as additions or changes to the interior, while the housing architecture interior remained a default square space.

Examining the Heritage of Public Housing Design in China

This common understanding of the interior space as a default, uncomplicated square is not a coincidence.

A visit to a Chinese city today reveals the same monotonous and generic design in housing apartments. Some scholars attribute this design model to the Soviet period in Russia. As philosopher Wang Hui observed, socialism was the door through which China passed on its journey into modernity, and it was Russia that opened the door by exporting models and expertise that formed the foundation for much of modern China.

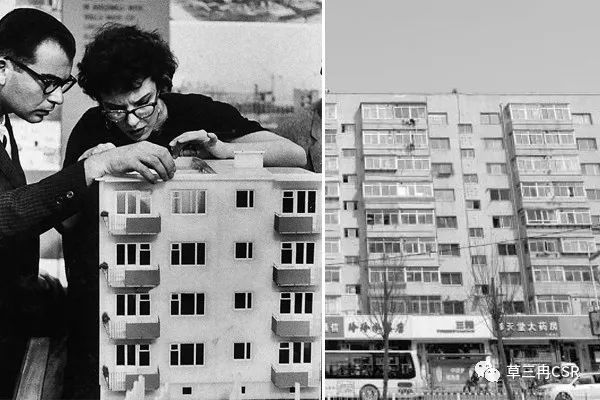

One example of Soviet-era housing design imported and modified in China is the Khrushchyovka, a type of low-cost, concrete-paneled or brick apartment building developed in the Soviet Union during the early 1960s. This housing model was imported and adapted in China as a political tool for the communist ideal of "everyone has a place to live."

In conclusion, the concept of "zhuangxiu" reflects the passion of people in urban China for making interior changes to their homes, especially given the monotony and standardized nature of apartment homes. The Soviet-era housing design, imported and modified in China, lays the foundation for the current design model of housing apartments in Chinese cities.

Floor plan of a Khrushchyovka

When I lived in Beijing, I experienced living in an apartment building for the first time. It was a five-story red brick building that I later found out was nicknamed the "Khrushchev Building".

What I was really excited about was having my own bathroom and kitchen in a small suite. No more having to go to the communal outdoor bathroom in the middle of the night! Sharing a public bathhouse was also a new experience for me and I was surprised to see so many naked bodies all in one place.

- Zhiyuan Xu, Home of the Rootless

What I was really excited about was having my own bathroom and kitchen in a small suite. No more having to go to the communal outdoor bathroom in the middle of the night! Sharing a public bathhouse was also a new experience for me and I was surprised to see so many naked bodies all in one place.

- Zhiyuan Xu, Home of the Rootless

khrushchev in shenyang

In this way, just imagining, probably you and your parents would have different bedrooms, and they could vary in their interior styles. However, the limited space would not provide much room for self-expression besides your bed and closet. This rigid and boring way of living is the same with the unit-based (danwei, 单位) working styles. Moreover, due to the lack of a living room and repeated housing types, the ritual of family gatherings that brings self-identity became impossible - the living scenario was collective and communities were unified.

The Crime of Ornament: the Interior Problems

A clear separation between design and decor has been evident since the very birth of modern architecture - along with a hierarchy. In the famous Ornament and Crime, Loos used the essay as a vehicle to explain his disdain of "ornament" in favour of "smooth and pervious surfaces," partly because the former, to him, caused objects and buildings to become unfashionable sooner, and therefore obsolete. This—the effort wasted in designing and creating superfluous ornament, that is—he saw as nothing short of a "crime." The ideas embodied in this essay were forerunners to the Modern movement, including practices that would eventually be at the core of the Bauhaus in Weimar. (Taylor-Foster)

For the Soviet Union rooted Chinese housing designs, the interiors are somehow designless. No ornaments and functionless elements were allowed. Determined by anthropometric rules (every daily action is measured accurately in numbers), the interiors were able to achieve the maximum spatial efficiency.

Khrushchyovkas featured combined bathrooms. They had been introduced with Ivan Zholtovsky's prize-winning Bolshaya Kaluzhskaya building, but Lagutenko continued the space-saving idea, replacing regular-sized bathtubs with 120 cm (4 ft) long "sitting baths". Completed bathroom cubicles, assembled at a Khoroshevsky plant, were trucked to the site; construction crews would lower them in place and connect the piping. Kitchens were small, usually 6 m2 (65 sq ft). This was also common for many non-élite class Stalinist houses, some of which had dedicated dining rooms. Typical apartments of the K-7 series have a total area of 30 m2 (323 sq ft) (one-room), 44 m2 (474 sq ft) (two-room) and 60 m2 (646 sq ft) (three-room). Later designs further reduced these meager areas. Rooms of K-7 are "isolated", in the sense that they all connect to a small entrance hall, not to each other. Later designs (П-35, et al.) disposed with this "redundancy": residents had to pass through the living room to reach the bedroom. Some apartments had a "luxurious" storage room. In practice it often served as another bedroom, albeit one without windows or ventilation. These apartments were planned for small families, but in reality it was not unusual for three generations of people to live together in two-room apartments. (Wikipedia)

Diagrams showing how each daily actions are carefully measured to achieve maximum spatial efficiency in design

One can easily imagine that living in the house was not a comfortable experience. The design was based on a standardized, impersonal figure, aimed at achieving a collective ideal. As a result, there has always been limited room for personal expression, which is where "zhuangxiu" comes into play.

The 1994 Invitational: Imaginary Alternatvies for Daily Escapes

Starting from the 1990s, the housing sector gradually became commoditized and the government implemented policies to introduce housing into the open market. As a result, vast lands were purchased and buildings were squeezed into the available space to achieve high efficiency and maximum profits. This high efficiency ensured maximized profits and since people, who were obviously excited over their ability to own and trade real estate properties, reacted overwhelmingly positively. This led to the formation of high-density, high-rising, and monotonous urban communities.

However, the rising property prices made it increasingly difficult for people to afford a house, which left them feeling a sense of absence and longing for a home. Property dealers were selling unfurnished apartments that looked cold, boring, and monotonous, which led to the popularity of “zhuangxiu” as a way for people to express their personality and have a sense of belonging and ownership of their spaces. During this time, a group of avant-garde artists created postcard illustrations for the newspaper Beijing Youth Daily (北京青年报), capturing people's reactions to the housing policy transformation. With the shift from government-owned to private dwellings, "zhuangxiu" became a keysite of consumption, drawing the attention of a newly boomed interior construction company, which funded a call for proposals that featured imaginative designs for "zhuangxiu". (1994 年艺术室内设计方案邀请展)

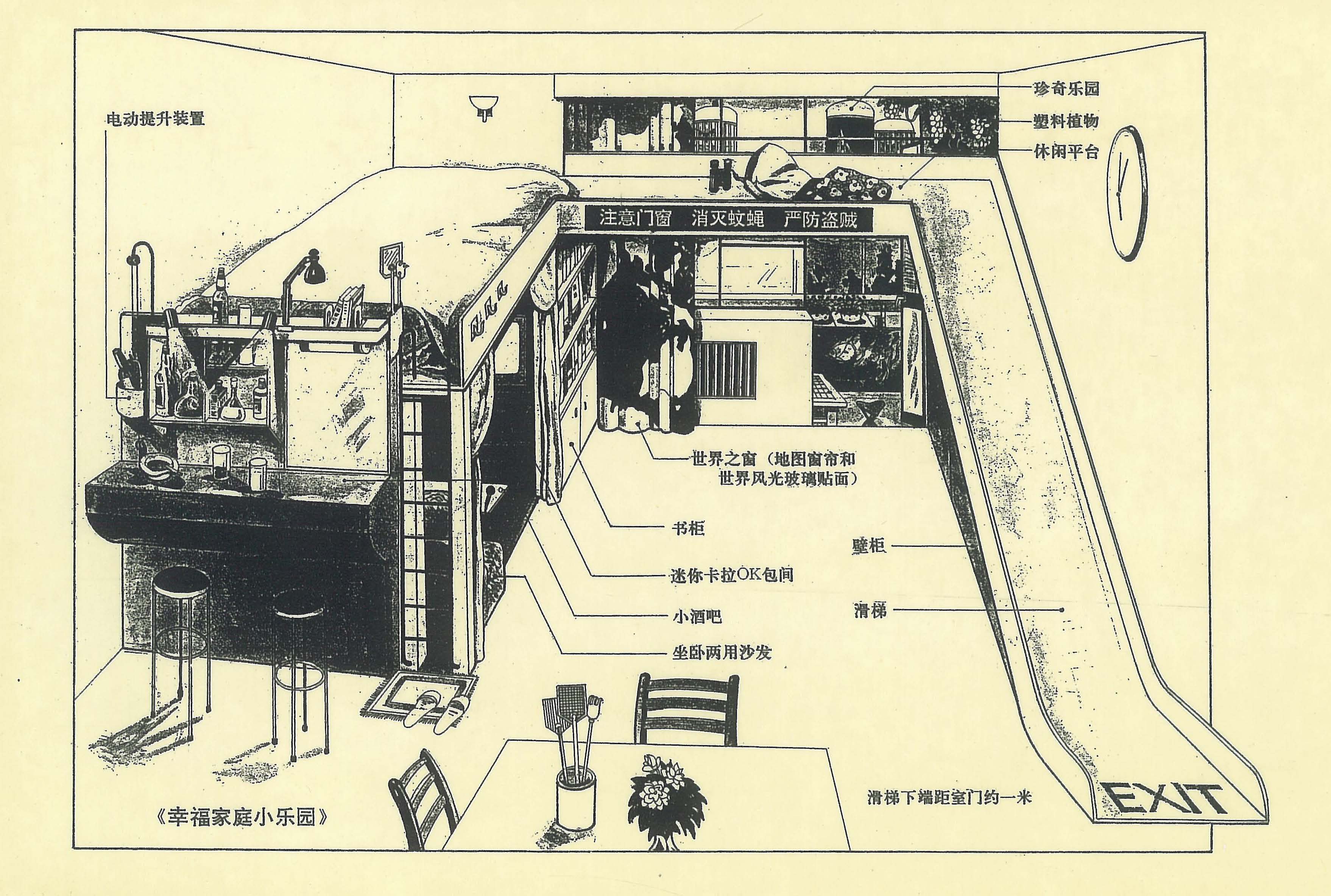

In his proposal illustration, Shaoping Chen (陈少平) divided the room into two parts by installing a platform and a slide. The top part with a bed was crowded and cozy, only providing enough room for one to crawl. Underneath the platform, a rich leisure life took place, with a minuscule bar, karaoke, bookshelves, and a sofa. Every entertainment activity was planned out so deliberately that no space was left unused in such a tiny room. Artificialness was the aesthetic in the little "fun land" designed in the back of the room, from the plastic plants to the door curtain "Window of the World" (printed with the world map and pictures of landscapes in different countries). Even the illustration was shown in monochrome, but the vibrant plastic colors made of everyday cheap consumer products found at that time were visible, much like what one would find in their grandparent's home. Serious annotations carefully explaining each element added more humor.

The most fascinating aspect of the design lies in its circulation. To move around the space, one must crawl onto the platform, slide down the children's slide, or peer through a telescope at the plastic plants. Additionally, an elevator has been included beside the bed, despite being unnecessary for practical reasons. This superfluous addition reflects the inhabitant's desire for amusement and personal expression within the confined apartment. Rather than being cramped and uncomfortable, Shaoping sees the lack of space as a deliberate attempt to create a cozy and intimate atmosphere.

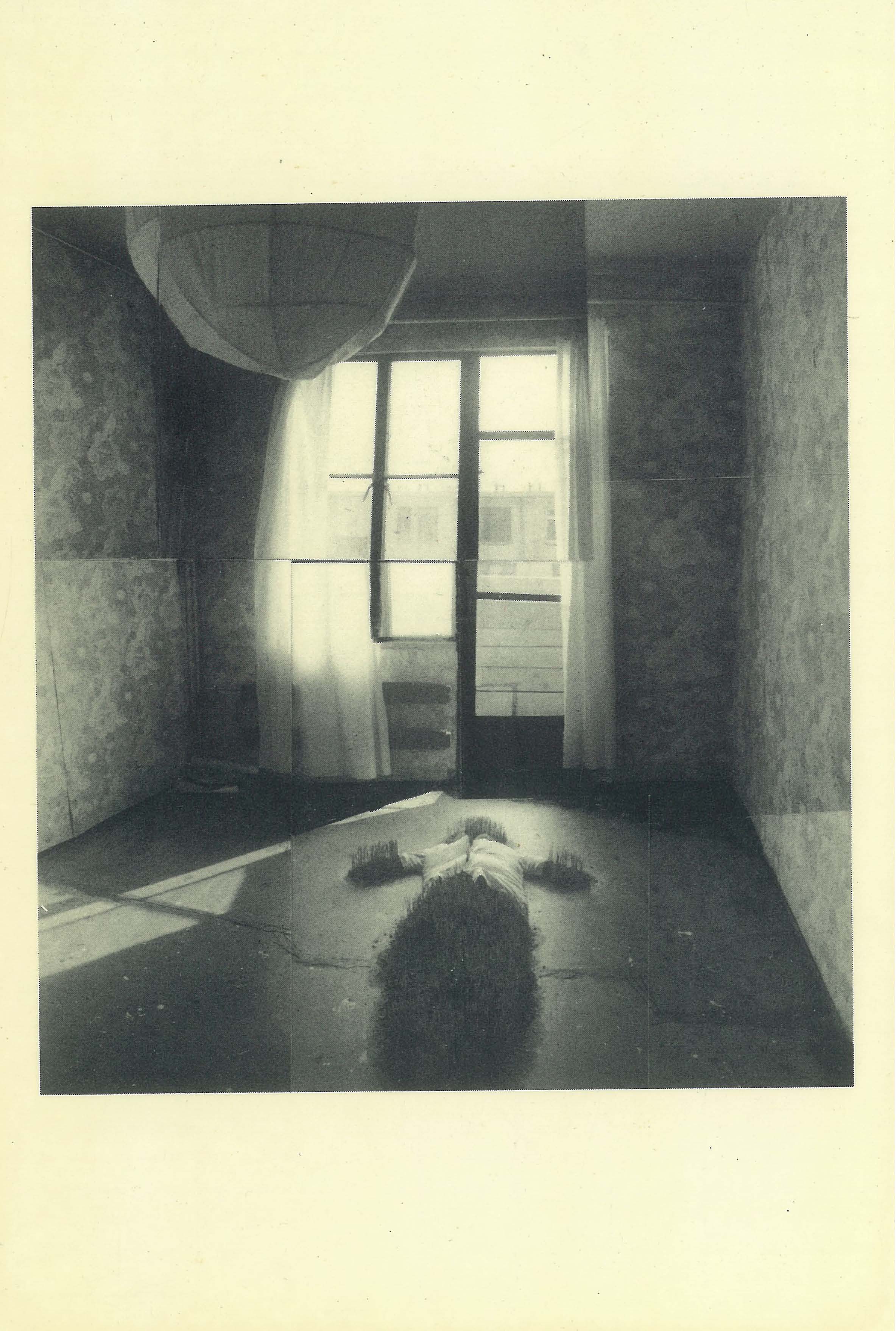

Artist Yongbin Li (李永斌) took a more poetic approach to interior design. In his sculpture, titled "Warm Family" (温暖家庭), Yongbin created a human-shaped area of grass wearing a white shirt on the floor of an empty room, along with handmade printed floral wallpaper and a lampshade. These elements created a sharp contrast with the brand new flooring and windows, as well as the blankness of the unfurnished apartment. According to Yongbin, the printed floral wallpaper, lampshade, and grass were made at different times to counteract the coldness of the "concrete space" and infuse the room with liveliness. .(墙面上的花布及灯罩、地面上生长的麦苗 , 都是在不同的时间分别制作完成的 , 但它们的共同目的都是为了驱走 “水泥空间”里的冰冷感 , 让居室内充满勃勃生机)

"Warm Family" is a process-based and time-based. Yongbin first made the printed floral wallpaper and lamp shade, and then added the grass in the shape of a human on the floor of the empty room. This approach reflects the furnishing and inhabiting process of a home space, and creates a contrast with the brand new flooring and windows of the unfurnished apartment. The handmade qualities of the wallpaper, lamp shade, and grass evoke strong emotions and stand in sharp contrast to the replicated and monotonous apartment. The concrete space feels stagnant in comparison to the changing and fleeting nature of the artwork.

Apartment info of Yongbing Li’s Home